Government officials and analysts point to a confluence of factors for what Energy Secretary Raphael Lotilla has called “a calamity”.

Pagasa, the government weather agency, recorded an “anomaly” increase in temperatures of 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) in April, compared to the 1991-2020 average, an Energy Department official said at the same briefing.

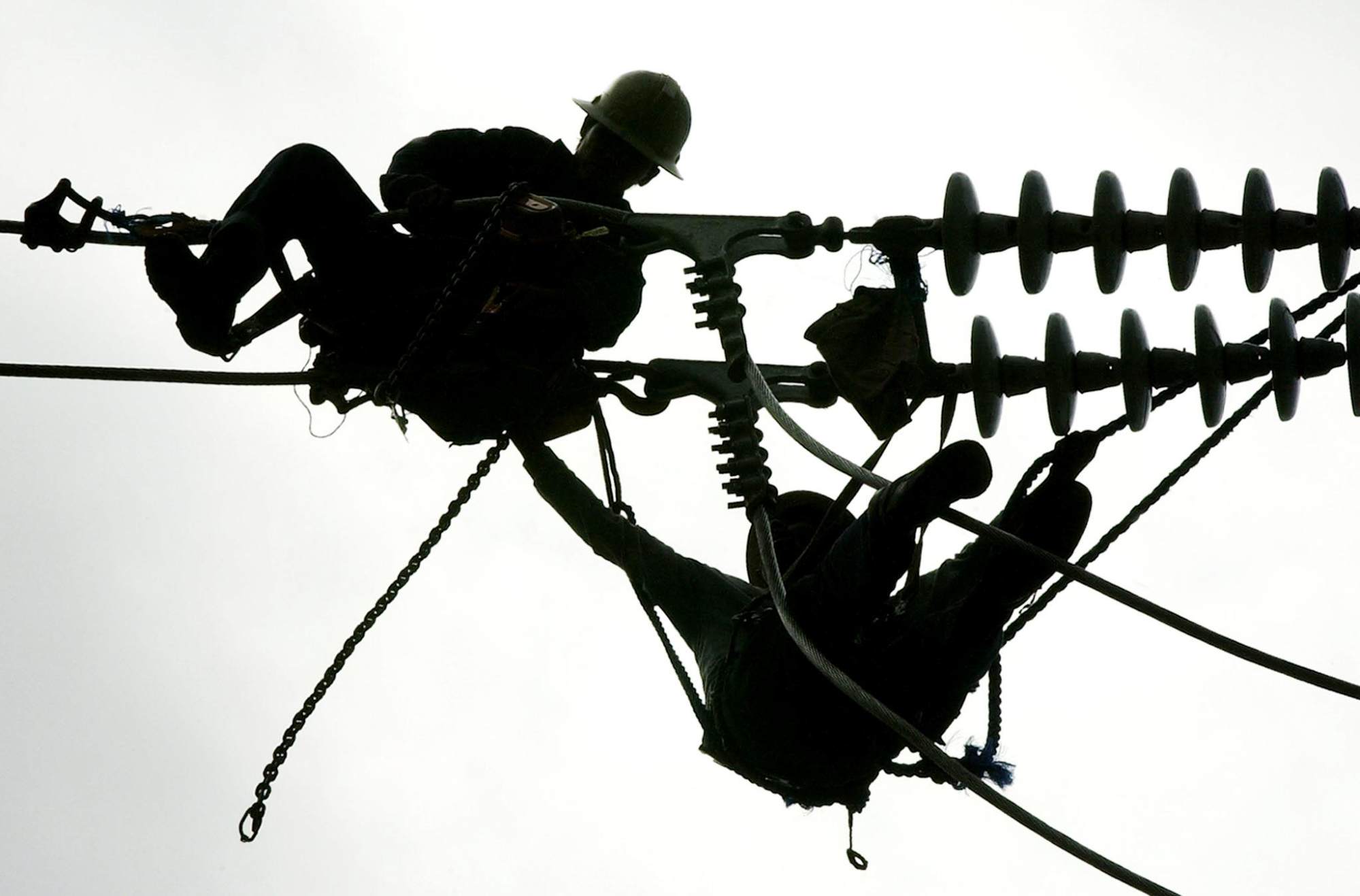

The intense heat forced 19 ageing power plants in the country’s industrial heartland of Luzon to shut down or be taken offline to prevent overheating, grid operator NGCP reported on April 16. The plants can currently only withstand ambient temperatures of up to 33 degrees, but Lotilla said efforts were under way to raise that limit.

Every five hours without electricity equates to economic losses of 556 million pesos (US$9.5 million) for the Philippines, Anne Estorco Montelibano, president of the Philippine Independent Power Producers Association Inc., said last year.

To address the energy crisis, Lotilla said the government took steps such as relying on more expensive bunker fuel plants, requiring large companies to use their own generators, and instituting a four-day work week in the public sector with temperature limits on air conditioning.

Up to 4.03 gigawatts of additional capacity could be added this year in a bid to resolve the crisis, officials promised at the April briefing.

Energy Undersecretary Rowena Guevara said at the time that the number of energy projects coming online this year would be “greater than the expected economic growth of the country”

The energy department projects capacity rising from 122,056 gigawatt-hours this year to 170,447 GWh by 2030 to keep pace with economic growth.

But two private analysts have called the government’s energy-saving measures a “stopgap” and blamed it for rising prices and falling capacity.

“We are now in a situation where the government cannot build power plants when needed, and the private sector is not required to build them even when needed,” Guido Delgado, former president of the Philippines’ state-run National Power Corporation, wrote on his blog last month.

The energy department’s sudden heavy reliance on renewable energy was a concern, said Boo Chanco, a business columnist for the Philippine Star newspaper who covers the sector.

Most of the 2.88GW of projects coming online this year involve renewables like solar, wind, hydro, biomass and storage, he told This Week in Asia, noting that solar in particular poses challenges, as its weather-dependent generation requires additional capital and expertise to connect to the grid.

Chanco, who is a former senior executive at the Philippine National Oil Company, warned in a column last month that extensive use of solar and hydro could destabilise the grid, degrade power quality, and raise consumer prices.

He told This Week in Asia on Monday that “increased pressure from international aid and financial institutions for faster renewable energy adoption” was the reason for the government’s current solar focus.

If trading partners require renewable energy to be used in manufacturing, Chanco said the Philippines’ exports could be affected, citing sources.

Renewables advocate Val Vibal, a member of the “Power for People” coalition of small energy consumers, told This Week in Asia that advances in renewable tech, including energy storage, have made intermittency issues more manageable.

He criticised the government for refurbishing ageing coal plants instead of shutting them down.

Vibal said Marcos’ use of windmill imagery during the 2022 presidential campaign was political posturing, as he has continued to rely on “dirty energy”.